Ladies and gentlefans, today we are talking about ancient Greek orthography.

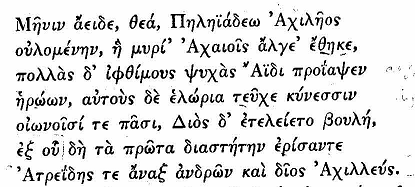

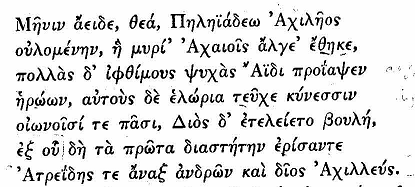

In modern Greek textbooks, the texts look something like this:

Homer, Iliad, Oxford Classical Text, late 20th century CE

Note the useful features of this text:

- mixed case

- accent and breathing marks

- spacing between words

- punctuation

- paragraph breaks and line breaks in poetry

All of these are very helpful for readers! Especially readers used to modern English orthography. But they are about as modern as the footnotes. This is not how the original (or "original", since this is Homer and he composed orally) text looked.

Sometimes you learn this in class! My Old English textbook has a section on reading manuscripts, with photographs for you to practice on. Sometimes you don't.

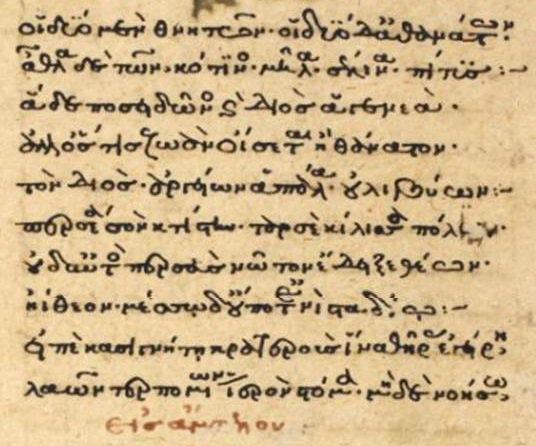

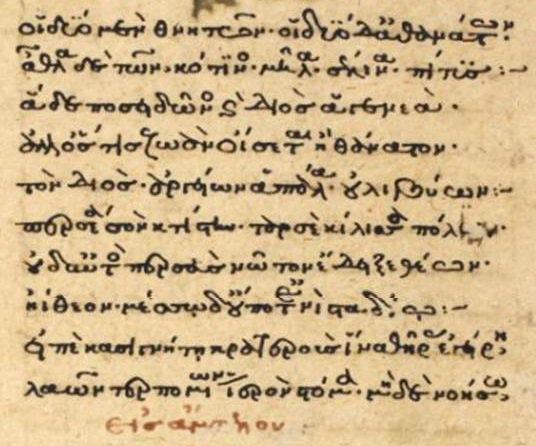

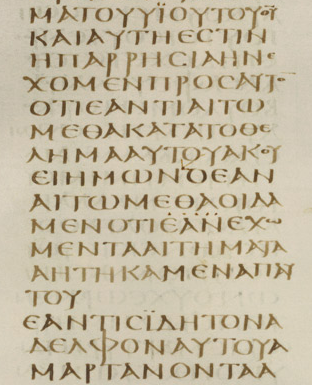

Here's a Byzantine manuscript:

Maximus Planudes, Anthologia Gracae, 14th century CE

Most of the features in the modern text above were introduced during the Byzantine empire!

This text has:

- accent marks

- punctuation

- paragraph and line breaks

All of which make things much easier if you're reading a text in an archaic form of your language that no one actually speaks anymore.

But it's mostly in single case, and there are no spaces between words.

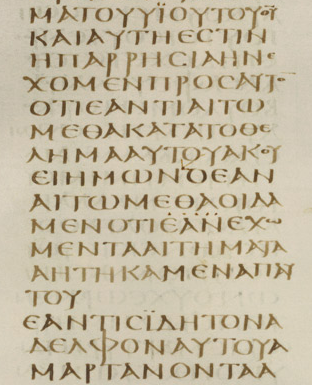

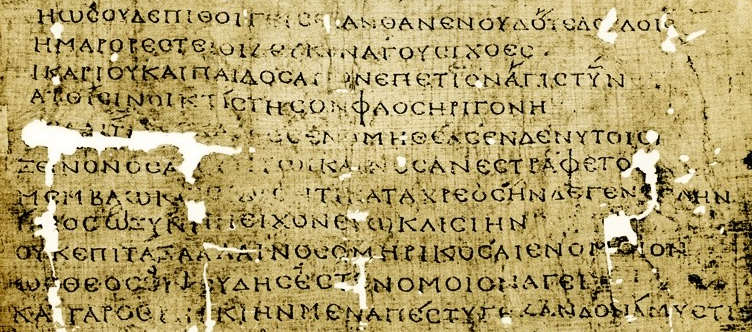

Here's a late classical codex:

New Testament, Codex Sinaiticus, 4th century CE

Note:

- single case

- occasional accents

- no word spacing

- a little punctuation

- paragraph breaks

If you're writing in the vernacular this is all you really need to understand a text.

But this is a giant formal church text most people would never see. And while it is an ancient Greek text, 4th century Christian Greece is not what most people think of when they hear "ancient Greek".

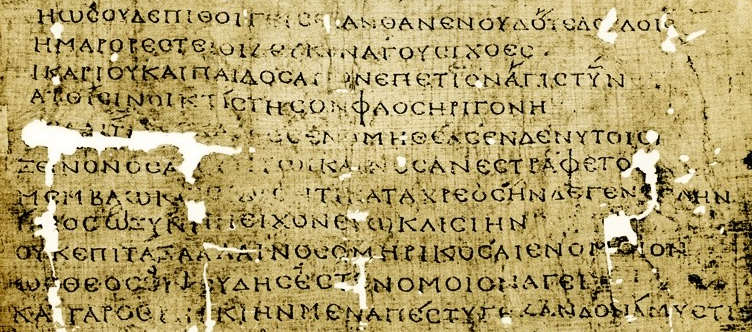

Here's a papyrus fragment:

Callimachus, Aetia, Oxyrhynchus papyri, 2nd century CE

Again:

- single case

- no accents

- no word spacing

- a little punctuation, maybe

- no paragraph breaks

Papyrus is time consuming to make! Parchment is ridiculously expensive! You want to save space. And at this point in time, you're writing in a language everyone understands! You don't need to provide all the extra help a student one or two thousand years later will need!

If you were writing a letter or a legal document, you might write it like this. Or you might write a letter on a wax tablet, and the recipient would erase it, reuse the tablet, and send it back to you with their reply. Informal texts don't survive both because they were written on fragile materials, and because no one thought they were worth preserving, the same way you don't carefully copy down and file your text messages.

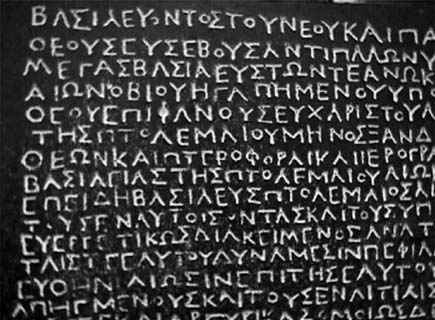

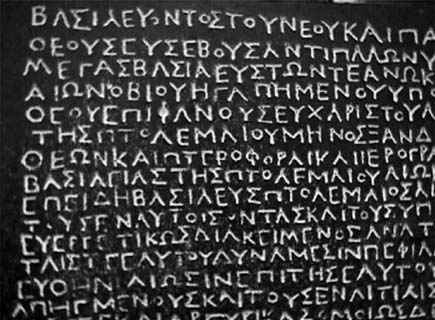

But the kind of longfom text your typical ancient citizen would see most often looked more like this:

Rosetta Stone, 196 BCE

This is part of the Rosetta Stone, which was a decree put on display in a temple. Note:

- single case

- no accents

- no word spacing

- no punctuation

- no paragraph breaks

You're carving this into stone! You are not wasting any space on that stone. And you're not putting in any extra marks you don't have to.

This text does have one modern convention that isn't a guarantee, though: the lines all go in the same direction.

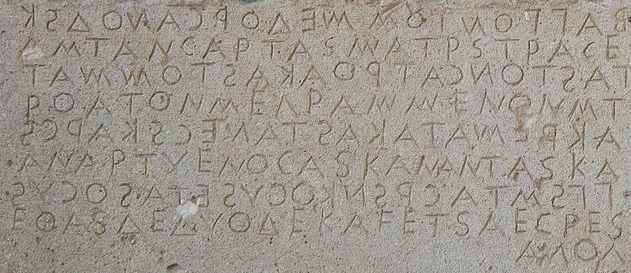

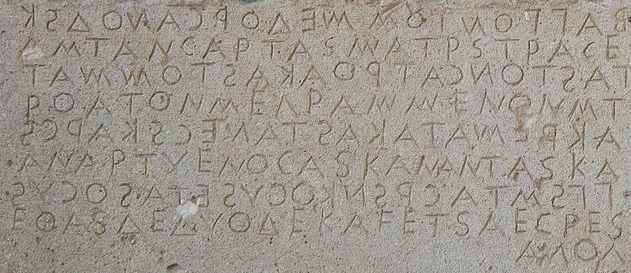

Gortyn Code, 5th century BCE

This is the actual law code of Gortyn in 5th century Crete, which was on public display in the agora. It's carved in boustrophedon, which is one of my favourite words. Boustrophedon means "as the ox turns" - that is, the same way you plow a field. The lines alternate which direction they go in: left to right, and then the next line is right to left, and then it switches again. This is most obvious for English speakers if you look at the direction of the epsilons (E, Ǝ).

Why would you do this? Well, it's a long walk to the other end of the stele for both reader and writer, so why not just start the next line where you already are anyway?

What we think of as normal formatting in a text showed up entirely within the last 2000 years. Because none of it is actually necessary! youcanunderstandtextwithoutitevenifyouareusedtohavingitthereitsjustabitharderandconveysfewerconnotationsandshadesofmeaningwhichyoudontneedinalawcodeanyway

In modern Greek textbooks, the texts look something like this:

Homer, Iliad, Oxford Classical Text, late 20th century CE

Note the useful features of this text:

- mixed case

- accent and breathing marks

- spacing between words

- punctuation

- paragraph breaks and line breaks in poetry

All of these are very helpful for readers! Especially readers used to modern English orthography. But they are about as modern as the footnotes. This is not how the original (or "original", since this is Homer and he composed orally) text looked.

Sometimes you learn this in class! My Old English textbook has a section on reading manuscripts, with photographs for you to practice on. Sometimes you don't.

Here's a Byzantine manuscript:

Maximus Planudes, Anthologia Gracae, 14th century CE

Most of the features in the modern text above were introduced during the Byzantine empire!

This text has:

- accent marks

- punctuation

- paragraph and line breaks

All of which make things much easier if you're reading a text in an archaic form of your language that no one actually speaks anymore.

But it's mostly in single case, and there are no spaces between words.

Here's a late classical codex:

New Testament, Codex Sinaiticus, 4th century CE

Note:

- single case

- occasional accents

- no word spacing

- a little punctuation

- paragraph breaks

If you're writing in the vernacular this is all you really need to understand a text.

But this is a giant formal church text most people would never see. And while it is an ancient Greek text, 4th century Christian Greece is not what most people think of when they hear "ancient Greek".

Here's a papyrus fragment:

Callimachus, Aetia, Oxyrhynchus papyri, 2nd century CE

Again:

- single case

- no accents

- no word spacing

- a little punctuation, maybe

- no paragraph breaks

Papyrus is time consuming to make! Parchment is ridiculously expensive! You want to save space. And at this point in time, you're writing in a language everyone understands! You don't need to provide all the extra help a student one or two thousand years later will need!

If you were writing a letter or a legal document, you might write it like this. Or you might write a letter on a wax tablet, and the recipient would erase it, reuse the tablet, and send it back to you with their reply. Informal texts don't survive both because they were written on fragile materials, and because no one thought they were worth preserving, the same way you don't carefully copy down and file your text messages.

But the kind of longfom text your typical ancient citizen would see most often looked more like this:

Rosetta Stone, 196 BCE

This is part of the Rosetta Stone, which was a decree put on display in a temple. Note:

- single case

- no accents

- no word spacing

- no punctuation

- no paragraph breaks

You're carving this into stone! You are not wasting any space on that stone. And you're not putting in any extra marks you don't have to.

This text does have one modern convention that isn't a guarantee, though: the lines all go in the same direction.

Gortyn Code, 5th century BCE

This is the actual law code of Gortyn in 5th century Crete, which was on public display in the agora. It's carved in boustrophedon, which is one of my favourite words. Boustrophedon means "as the ox turns" - that is, the same way you plow a field. The lines alternate which direction they go in: left to right, and then the next line is right to left, and then it switches again. This is most obvious for English speakers if you look at the direction of the epsilons (E, Ǝ).

Why would you do this? Well, it's a long walk to the other end of the stele for both reader and writer, so why not just start the next line where you already are anyway?

What we think of as normal formatting in a text showed up entirely within the last 2000 years. Because none of it is actually necessary! youcanunderstandtextwithoutitevenifyouareusedtohavingitthereitsjustabitharderandconveysfewerconnotationsandshadesofmeaningwhichyoudontneedinalawcodeanyway